Blog post

The VIPs – Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines

Energy Blog, 9 December 2021

The VIPs of Southeast Asia: Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines. What’s next for renewable power?

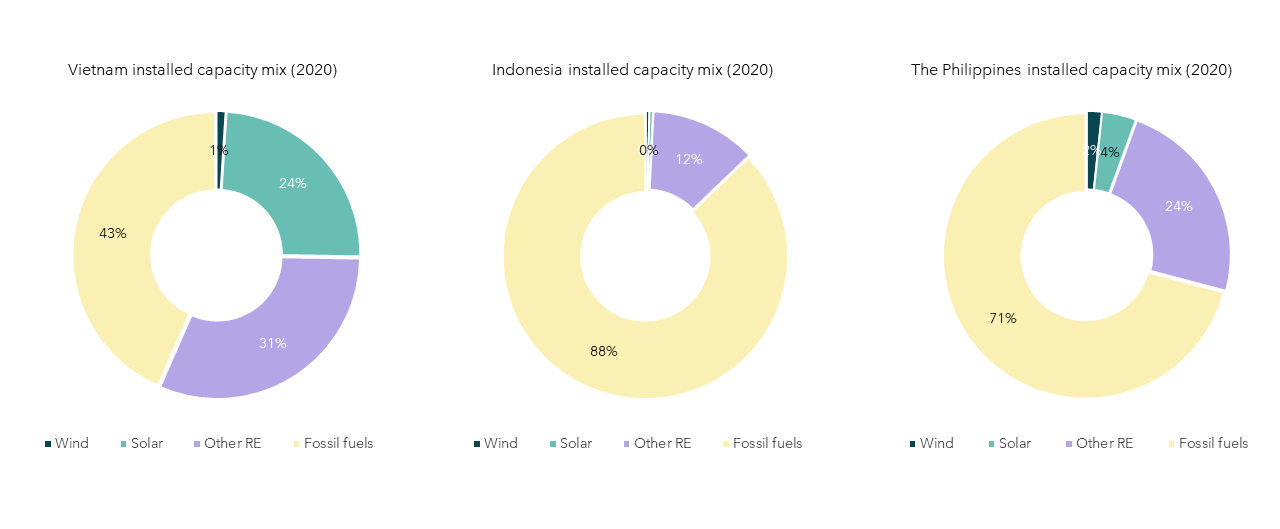

Southeast Asia is a region that, despite having a total population of 667 million and a combined GDP that would form the sixth-largest economy in the world, is largely overshadowed in the context of renewable energy. This is understandable because this is a region that seems to have an acute addiction to fossil fuels and the majority of the region’s electricity supply still comes from fossil fuel sources despite each of these countries possessing vast amounts of renewable energy potential. Below is a quick overview on the power generation situation in each country:

Vietnam is an exception where its hydropower potential has been almost fully realised – and it experienced a boom in solar installations, which will be covered later.

In this blog post, we analyse what has happened and what could be next for these VIPs.

Vietnam – a lone star amongst the VIPs

The hottest country amongst the VIPs, Vietnam has installed ~16 GW of solar PV capacity during 2019-2020. To put this into perspective, solar capacity in 2018 was 105 MW. This happened despite no shortage of literature, experts and developers complaining about the “non-bankable” and non-negotiable PPA template with EVN (the sole state-owned electricity provider). The fact is that being one of the few countries in the region that presently has an actionable and attractive FIT in place was enough to catalyse the boom. There are other things going right for Vietnam: tax incentives, relatively clearer development process and more straightforward path towards site control but the main draw is the certainty and predictability of the tariff rate, a rare commodity in the region these days. Moreover, another factor is the interest of local and regional players who appreciate that smaller solar PV can be economical and local banks are comfortable taking counterparty risk of the offtaker (EVN).

So what is next for Vietnam after such a blistering pace of growth? There have been enough reports of grid overload and curtailment to conclude that the next step is to invest heavily into the upgrade of the country’s transmission lines and/or to find a solution to balance out the huge installed solar capacity. The authorities, perhaps in recognition to this problem seem to want to double down on coal instead; in the latest (Oct 2021 at the time of writing) draft of the Power Development Plan 8 (PDP8) the coal power capacity target has been increased at the expense of about 4 GW of onshore wind and a complete removal of offshore wind from PDP8’s 2030 base scenario. The latter is definitely a missed opportunity for a country with over 160 GW of offshore wind potential. This is a spanner thrown in the works just as Vietnam is catching the attention of international investors.

Other than that, the same challenges remain going forward: the PPA template still needs to be improved and the grid needs to be strengthened in time to allow for more intermittent renewables. These challenges did not seem to slow down development so far because solar projects tend to be smaller in size and thus can still be financed by the local banks, but it remains to be seen whether the same challenges can be overcome by larger wind projects. Moreover, the lack of a follow-up to the FIT regime for wind and the recent PDP8 draft change will also be damaging to investor sentiment, but I would not bet against Vietnam remaining the best place to develop renewable energy in Southeast Asia at this moment. If the government approves a framework for direct corporate PPA, independent power producers will be able to sell power directly to many multinational companies which have pledged to be carbon neutral. Watch this space!

Indonesia – the land of perpetual potential?

Renewable energy development in Indonesia has gone through a few ups and lots of downs. In 2015, attractive FITs were introduced by the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR) for hydro and solar power but then in 2017 the MEMR introduced a new scheme to reduce the average power price. All new projects must offer tariffs to the sole state-owned electricity provider (PLN) that are lower than either 85% or 100% of each province / region’s own cost of production (the infamous “BPP” as it is affectionally called in Indonesia).

Notwithstanding the annual moving target that developers need to follow closely, the calculation method for the annually published cost of production is also as mysterious as the ingredients for the classic Dutch snack called Frikandel (it is a yummie snack but apparently you do not want to know what it is made of). This is coupled with many other barriers: land acquisition issues, PLN’s intermittency phobia, PLN’s reluctance in signing new PPAs (due to them signing too many coal-fired PPAs in the past decade) and unrealistic local content requirements. As a result, wind and solar contribution to the total electricity mix has barely moved in the past 5 years.

Is it all doom and gloom then? I think the answer is no; Indonesia, the largest economy in Southeast Asia will inevitably require renewable energy to supply the growth in power demand and it has pledged to reach carbon neutrality by 2060. It would be a mistake to exclude Indonesia from your portfolio but in the short term, I will opt for the term “cautiously optimistic”. There is supposedly a Presidential Decree detailing FITs for various renewable energy technologies (expected to come out next year, every year since 2019!), rooftop solar projects can now sell excess electricity back to PLN at 100% of tariff instead of 65% and a few announcements recently on large-scale solar plant developments show that developers continue to be optimistic on Indonesia’s potential.

The FIT rate was the spark that started significant renewable development in both Vietnam and the Philippines, and hopefully that is replicated in Indonesia when it is finally released and implemented. Finally, reportedly around 50% of the planned new capacity additions in the new 2021-2030 electricity business plan will come from renewable energy, with a large portion being solar. If I turn my sceptic switch off, I would say that these developments really look promising.

The Philippines – is it more fun in the Philippines?

This is the actual slogan from the Philippines tourism board – but obviously depends on your definition of “fun”, and the same goes for its power market. The electricity market in the Philippines is more complex (so… more fun?) than those of the neighbouring countries’ as it is more liberalised. Moreover, a connection to the southern island of Mindanao is scheduled to come online in the coming year, thereby finally connecting all the Philippines’ main islands in one grid.

The Philippines is perhaps one of the earliest to implement a FIT regime in the region, and for some time, it saw successes. In the period from 2014 to 2016, ~765 MW and 427 MW of solar and wind capacities were added to the grid, from negligible numbers before the FIT. This growth materialised despite the restricting foreign ownership law (40% maximum) and the fact that back in 2014, solar prices had not dropped as dramatically as it had in recent years. However, the FIT program was not extended and activity in the Philippines has slowed down dramatically as a result.

Despite the lost years, the Philippine government is still taking steps to promote RE development; the Department of Energy (DOE) had called for a moratorium on greenfield coal plants to shift to a “more flexible supply mix”. This meant the only other “low carbon” option for a flexible and reliable source of electricity would be natural gas.

However, gas-fired power plants mean long development periods and a huge amount of investment because LNG would have to be imported and, with the recent run up on gas and coal prices, you could be wondering why the Philippines wants to continue to increase their bets on fossil fuels. How else to fill the gap then? Answer: renewables (duh!). The DOE had, more than 10 years ago, set a target of 35% share of renewable energy generation by 2030 but as of the end of 2020, it is still only about ~21%. The Philippine government is now trying to achieve this target by introducing the Green Auction Programme, which would be applicable to all distribution utilities (DUs) that are required to produce or purchase a certain percentage of clean energy. This auction programme was slated to be implemented this year with a total capacity of 2 GW, but the implementation of the auction is in danger of being delayed as the price ceiling has not yet been determined by the Energy Regulatory Commission and the presidential election next year will do anything but help speed up any policy making.

Despite all this, developers would be wise to explore offshore wind as early as possible to capture the best sites, because the Philippines has at least 170 GW of offshore wind potential (with none tapped so far and a handful of projects in early-stage development) and as offshore wind is relatively less intermittent than solar / onshore wind – it could be the preferred renewables source in the future.

Conclusion

Each of the VIP countries has its own dynamics that I could not hope to have captured in its entirety with just a couple of paragraphs, but hopefully this blog gives you a sense of the excitement and frustration that resides in the region (okay, mostly frustration for now). The energy transition in Southeast Asia is happening slowly… the developers who can hold their breath the longest will reap the rewards when the locks are finally (creaking) open. If the past decade is the decade of false dawns, this decade should hopefully be the decade of daybreaks.