Blog post

Why Hinkley Point is unlikely to get built

Energy Blog, 4 July 2017

Jérôme Guillet looks at the reasons why Hinkley Point C nuclear power station is unlikely to ever get built.

The Hinkley Point nuclear project in the UK is a long running saga, and it currently looks like it’s finally going to happen, after decisions by both the UK government and the board of EDF to go ahead with the project. Some early works have started (behind paywall) and full construction is now scheduled to go ahead in 2020 with operations starting in 2025. But new developments in the offshore wind markets, plus some of the complications associated with Brexit, are increasingly likely to both derail it and offer a way out.

The big story in the past year in European power generation has been the record low prices reached in offshore wind tenders in Denmark and the Netherlands, with power prices in the 50-70 EUR/MWh range, including transmission (and intermittency) costs. This concluded with the startling result of “zero bids” in Germany where the bidders are actually willing to build projects with no direct government support other than the provision of the grid connection (valued at ca. 10-15 EUR/MWh). While the German tender outcome may be the result of very specific and unique factors (small volumes tendered, projects to be built only in several years’ time, additional layer of complexity due to limited grid access within clusters in addition to the overall price competition), the low prices seen in the other recent tenders are highly likely to be replicated soon in upcoming tenders.

Such price levels are granted to offshore wind projects, just like Hinkley Point, under so-called “contracts for difference” (CfDs). Under these contracts, a public entity pays to a given project a top-up corresponding to the difference between the fixed level set under the tender (the “strike price”) and the market price received by the project. These contracts give price certainty to projects and allow them to go ahead with the heavy upfront investments required for their construction. Hinkley Point benefits from a strike price of 92.5 GBP/MWh (or 89.5 GBP/MWh if two units are built). Setting aside the different currencies, the biggest differences between Hinkley and the offshore wind projects are that the Hinkley CfD is:

(i) set to last 35 years (vs. 15 years in the Netherlands and even shorter in Denmark), and

(ii) indexed to inflation (whereas the offshore wind tariffs are fixed).

This means that after 15 years, offshore wind will see its price support, still at 50-70 EUR/MWh, end, while Hinkley will have a guaranteed price of ca. 135 GBP/MWh (assuming 2.5% inflation per year) with 20 more years to run.

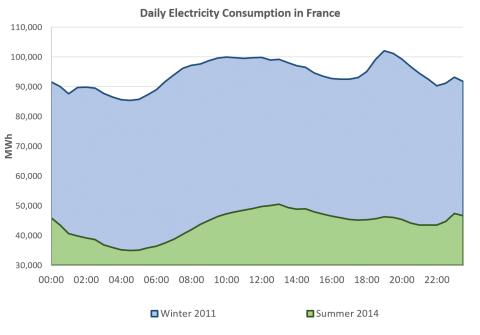

This might be defendable if nuclear was providing something much more valuable than offshore wind, but it is increasingly hard to argue that this is the case. Nuclear plants typically run at a capacity factor of 90%, i.e. they run at the equivalent of full power 90% of the time (although the average French fleet is closer to 75%) and provide “baseload” power, i.e. a constant supply at all times, which may sound like a good thing but is actually not necessarily adapted to the demand for electricity, which typically varies by a factor of two during the course of a day but can vary by a factor of three during peak demand days. Offshore wind now has an average capacity factor of 50-55%, so provides on average only one third less electricity per installed MW than nuclear, but has a production profile which is actually easier to integrate into the power system, with peak production in the mornings and evenings, when demand is strong, and more in winter than in summer, which similarly fits demand patterns in Europe. This means that 5 GW of offshore wind will provide as much power on average as Hinkley Point’s 3.2 GW, with a production profile that will be as easy – or easier – to manage as/than that of a nuclear plant. And an offshore wind farm takes two years to build, compared to the five to ten years (or more) that recent nuclear power plants have required.

Average French electricity demand over 24 hours (source: FranceInfo/RTE recover data)

Europe is lucky to have the North Sea, a huge area with very low water depth, where it is possible to build a lot more offshore wind farms than we’ll ever need, bordering the UK, Germany, Denmark, Belgium, and the Netherlands (and to a lesser extent France). At prices such as those reached in last year’s auctions, governments will see it as an easy decision to encourage the buildup of a lot more offshore wind than has been achieved to date. This will make the need for new nuclear generation even harder to justify in those countries still considering the technology. Prices in the Netherlands and Denmark, relatively small countries, might have been seen as flukes (even if we now have four successive tenders with such low prices), but the extraordinary result of the tender in Germany should put this notion to rest, and the forthcoming second CfD auction in the UK and third tender in France later this year are highly likely to see similarly low prices. That will send a signal that simply cannot be ignored in these countries. With the first projects at such low prices to be operational in the Netherlands and Denmark by 2019-2020, i.e. before Hinkley Point’s full construction even starts, and projects under construction in the UK at prices in the, say, 60 GBP/MWh range, the pressure to abandon the Hinkley project as wasteful and unnecessary is going to be massive. There’s been persistent criticism of the Hinkley Point tariff in the UK even when the alternative was not so obvious (including, most recently, from the National Audit Service). The expected data points from the forthcoming offshore wind tenders will create an immediate and obvious focal point and additional argument against Hinkley Point’s tariff level.

Naysayers will say that there are days with no wind in the North Sea, and we thus need to build backup in the form of new gas-fired plants. That is actually an argument with limited practical impact. We happen to have a surplus of gas-fired plants that are used very little right now, and can certainly be used for that purpose with minor technical tweaks. We also know that the grid is able to handle vastly larger levels of renewable energy penetration than we thought possible even a few years ago (and indeed adapts on an ongoing basis to handle yet more). So the issue is not technical, but commercial and economic. It is certainly true that we need new regulatory frameworks that make it possible (and profitable) for gas-fired plants to be available for occasional needs only rather than the more regular use they were originally designed for, although some solutions to that actually exist. Further, evidence shows that intermittency risk is quite limited: the current risk premium for long term renewable “direct marketing agreements” in Germany (which essentially set a price for the intermittency risk, which by law renewable energy projects must now bear in full) is around 1 EUR/MWh, i.e. extremely low. And carbon emissions from such limited use of gas-fired plants will be low – we’ll need a lot of gas turbines, but not a lot of gas (and incidentally the former are manufactured in Europe whereas the latter is now mostly imported, even in the UK).

Given the perceived strategic nature of the project, it is hard to see Hinkley Point being dropped without a serious crisis between and within the French and British governments, not to mention the leadership of EDF, and the Chinese angle given the presence of Chinese co-investors. Without such a crisis the project might very well be kept alive due to inertia and longstanding political commitments. But this is where Brexit comes in, with one of its many intractable issues being what will become of Britain’s participation in Euratom, which supervises and regulates all nuclear activities in Europe, but is part of the EU institutions and thus supervised by the European Court of Justice, which the British government has vowed to get away from. No nuclear trade can happen without such regulation, and Britain will need to set up a whole new regulatory framework, and negotiate new arrangements with the US and Europe, both of which are indispensable for any nuclear plant to be run.

There will thus be growing pressure to ditch the Hinkley Point project given its expensive power price arrangement, and the uncertainly over Euratom will offer an excuse to both EDF and the UK government do it without causing a full-blown political and diplomatic crisis.

The UK will actually be better off with such a decision; the biggest victim in the short term will be EDF, which will see its ambitions thwarted, but that may actually end up being seen as a blessing in disguise, as the company drops a highly risky project (which has been controversial even within the company, triggering the resignation of its CFO, Thomas Piquemal, last year, and is now officially acknowledged to cost at least two billion euros more than planned) and is forced to reconsider its “nothing-but-nukes” strategy. Better to do this now, when it is still possible to transition to renewable energy, rather than be committed for another 50 years or more to a technology which, while successful in the past 40 years, is no longer competitive today.

And Europe as a whole can get rid of its coal and nuclear fleets (in that order preferably, even if Germany has chosen to do it the other way around) in a relatively short period.

Jérôme Guillet co-founded Green Giraffe in 2010 and was a Managing Director until 2021.